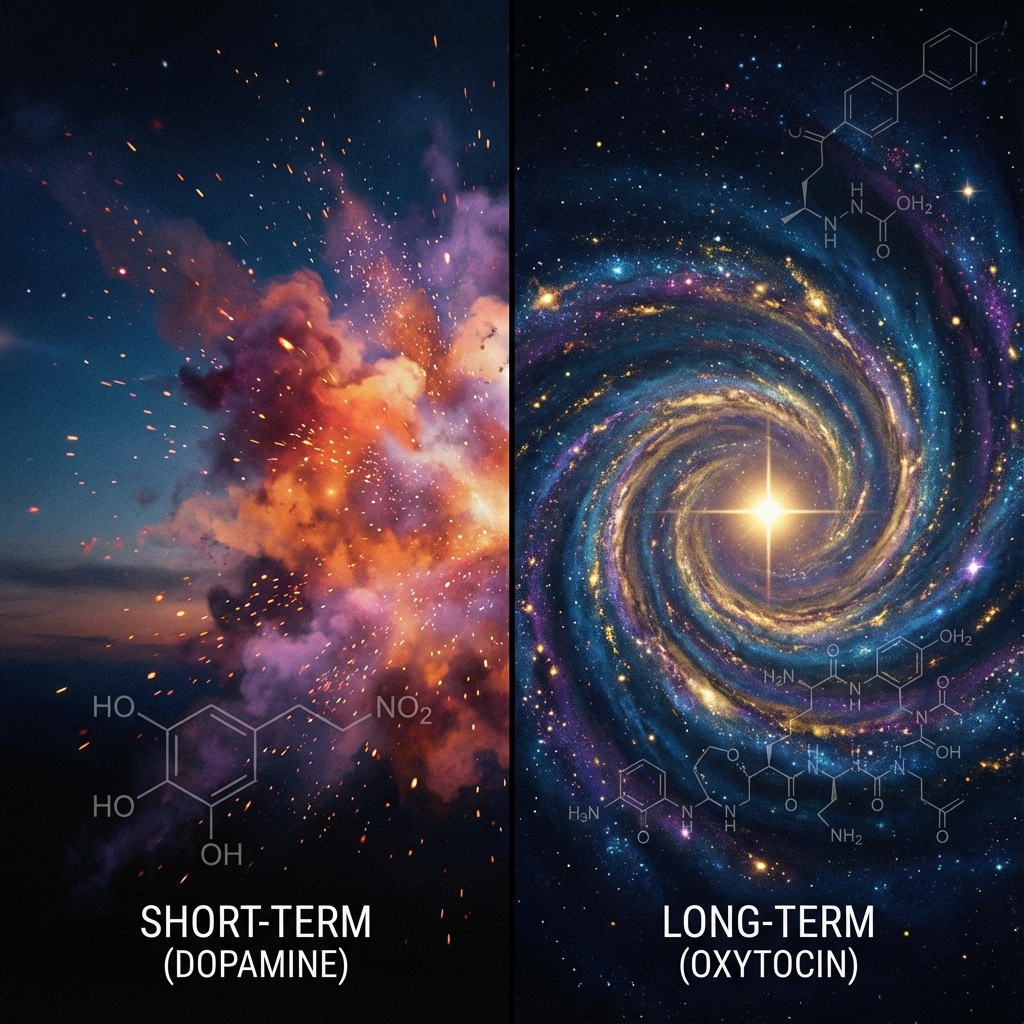

I wrote once about fireworks and stars, about the fever of falling fast and the quiet patience of love that holds. It was poetry, born of feeling. But poetry, it turns out, is often just science we haven't yet named.

The fireworks I described—that breathless, burning rush of new love—have a neurochemical signature. Deep in the brain sits a tiny factory called the ventral tegmental area, or VTA. When we fall in love, this factory works overtime, flooding our neural pathways with dopamine, the molecule of desire and obsession. Anthropologist Helen Fisher, who has spent decades studying the neuroscience of romance, describes it plainly:

"Dopamine is key. This neurotransmitter is the central component of the brain's reward system—the brain system that gives the lover focus, energy, motivation, and craving for the beloved."

Craving. That's the word. Not contentment. Not peace. Craving—like hunger, like thirst, like the desperate need for a drug. And that comparison isn't hyperbole. Fisher's fMRI studies revealed that new lovers show brain activity identical to cocaine addicts. The same reward circuits light up. The same obsessive patterns emerge.

"Romantic love, at its best, is a wonderful addiction. At its worst it leads to depression, suicide and even murder."

The fireworks, then, are quite literally a kind of madness—a chemical storm that commandeers the brain's decision-making apparatus. Research has shown that serotonin levels in people newly in love resemble those found in individuals with obsessive-compulsive disorder. We cannot stop thinking about them. The red flags, as I wrote, burn pretty in that light.

But here is where the science becomes beautiful: we develop a tolerance. Just as with any drug, the dopamine high cannot sustain itself. After about twelve months, the fever fizzles. The fireworks fade. This is biology's design, not love's failure.

And what rises in their place? The stars.

Psychologist Robert Sternberg identified this shift decades ago in his triangular theory of love. Early passion—all heat and urgency—is but one vertex of the triangle. The other two are intimacy and commitment. Passionate love is present-focused, consuming, temporary. Companionate love, built on intimacy and commitment, "endures and grows over time with deep meanings."

The molecule of the slow burn is not dopamine but oxytocin—the so-called "bonding hormone." Unlike dopamine, you don't build a tolerance to oxytocin. The benefits compound. Professor Ruth Feldman at Bar-Ilan University has studied couples through the early stages of romance and found something remarkable: those with higher oxytocin levels stayed together longer. They finished each other's sentences. They laughed together. They touched more often. The hormone of attachment predicted the longevity of love.

"When oxytocin stimulates dopamine's rewarding properties, euphoric feelings result. This explains why long-term relationships are so satisfying."

The slow burn, it seems, is not the absence of fire but a different kind entirely. Stars, after all, are fire—nuclear furnaces burning for billions of years because they found a way to sustain themselves.

And the science tells us something even more hopeful. A 2011 study at Stony Brook University scanned the brains of couples married an average of 21 years—and found the same dopamine-rich reward activity that appears in the newly infatuated. The researchers concluded that it is possible "to remain madly in love after decades of marriage." The stars, when tended, can burn as brightly as fireworks ever did.

Dating experts now have a name for what I described: the slow burn relationship. Relationship researcher Logan Ury puts it simply:

"Some of the best relationships come from a slow burn rather than a spark."

The logic is intuitive once you see it. Sparks are reactive, quick to ignite and quick to extinguish. But love built slowly—on friendship, on accumulated understanding, on the patience of two people learning each other—develops stronger foundations. Your emotional investment grows proportionally to how well you know them. You make better choices. You feel more secure. You build trust that can withstand the pressures that shatter quicker flames.

So when I wrote that I want someone who will watch with me the humble show the heavens have played for billions of years, I was writing neuroscience without knowing it. I was writing about oxytocin's steady accumulation, about dopamine's integration into sustainable patterns, about the brain's capacity to find deep reward in long commitment rather than short intensity.

The fireworks are not wrong. They serve their purpose—they get our attention, they bring us close, they give us the energy to begin. But they are not the end. They are not even the best part.

The best part is after the finale, when the smoke clears and the quiet returns. The best part is looking up and realizing the sky has been full of light all along—patient light, ancient light, light that will still be burning long after the last spark falls.

This piece is a companion to Slowburn, which explores the same themes through metaphor alone. Sometimes poetry needs no proof. Other times, it's nice to know the universe agrees.